Chapter One

Sunday, March 28th, 2010

Danny Sanchez arrived at 10:27.

It was already bedlam; hundreds of people covered the dusty patch of waste ground beyond the white walls of the property, shouting, pushing, arguing among the cacti and scruffy palms. The excavator’s arm loomed menacingly above the roof of the two-storey villa.

The demolition had been scheduled for nine a.m., but frantic negotiation had earned the elderly expat owners a three-hour stay of execution while the house was cleared. The whole neighbourhood turned out to help, Briton and Spaniard alike. A stream of people walked back and forth along the edge of the unpaved road, carrying everything and anything they could salvage – doors, windows, even the kitchen work surface. The problem now was where to put it all. An incongruous pile of household items was collecting around the trunk of a fan palm. Danny watched as a negligee blew free from a box and wrapped itself around a cactus.

Christ, what a mess.

In eighteen years of journalism, Danny had witnessed dozens of horrors – people cut from the wreckage of car accidents, a woman leap from a burning building, a suicide on a railway track – but this was something new. They were going to demolish Peggy and Arthur Cookes’ house and nothing could be done to avert it. He’d seen the paperwork. Nearly every penny the poor old duffers had was invested in the villa; a lifetime’s equity would be smashed to rubble. It was like waiting for an execution.

The Junta de Andalucía, southern Spain’s regional government, had sent a woman in her mid-thirties to oversee the demolition. Crafty, Danny thought; people found it harder to get angry with a woman, especially an attractive one. Her hard hat and fluorescent bib bobbed at the centre of a tightly-knit group of people. Guardia Civil officers in green boiler suits formed a protective ring around the Junta woman. Then came the leaders of the protestors, waving documents and trying to argue over the shoulders of the Guardia officers.

Behind them was the press pack, two dozen strong, cameras and microphones waving above the crowd as it surged and rocked. Gawkers and curious children milled at the edges, wondering what all the fuss was about.

For her part, the woman from the Junta looked genuinely distraught at what she had to do. Danny had no idea whether she could follow the English words being bellowed at her, but it was obvious she understood the gist. She kept pointing to the paperwork on her clipboard, raising hands and shoulders in shrugs of helplessness. Someone, somewhere had decreed the demolition must go ahead; it was her job to get it done.

The Cookes were inconsolable. Peggy sat on an armchair that had been dumped among spiky clumps of esparto grass. Tears carved streaks through the dust that had settled on her face. Danny recognized the armchair; he’d sat in it when he’d interviewed them a year before, when the demolition orders were first served. Arthur Cooke had looked dapper and defiant as he posed for the cameras back then; now, every one of his seventy-three years weighed upon him. He stood with his hand on his wife’s shoulder and turned moist eyes as Danny approached.

“Not now, mate,” he said, shaking his head. “The bastards are about to ruin us.”

Danny nodded, glad he’d been spared having to ask the obligatory “How do you feel?” It was amazing how dumb those four words could make you feel sometimes.

Peggy Cooke wanted to speak, though. “Why us?” she said, her voice shrill. “Out of all the hundreds of people, why does it have to be us? I want you to print that. It’s not fair.”

Why us? That had been everyone’s first reaction in March 2009 when the judicial demolition orders were delivered to eleven different families dotted around the municipality of Los Membrillos. It seemed so monstrously unfair, given the scale of the problem in Almeria, the province that occupies Spain’s south-eastern tip. A Junta survey had uncovered more than 12,500 irregular constructions in just ten of the worst affected municipalities. But the Spanish legal system was a Heath-Robinson contraption manned by characters from Kafka; immense and baffling in its complexity, arbitrary in the decisions it dispensed and spitefully prescriptive when it did so. It was one of the dangers of emigrating to Spain, the flipside to all the sunshine, fiestas and good living.

Not that it had worried the tens of thousands of Britons who had flooded the Almanzora Valley at the turn of the century, buying up villas and plots of land for self-builds, breathing life into the moribund rural communities that nestled below the Sierra de los Filabres mountain range. But the rush to expand had left thousands caught in the legal quicksand between the local and regional government of Andalusia. Local councils could grant licences to build, but the regional government had the right to challenge those licences. The catch-22 was that no one would stop you from planning to build a house; the house actually had to be built – and the money spent – for it to come to the Junta’s attention and challenge its legality.

Why us? Danny knew the answer to Peggy Cooke’s question; he’d interviewed the mayor of Los Membrillos. “We had so many applications for building licences, we were swamped,” the mayor had said, unlocking a cabinet and indicating three large cardboard boxes leaking paperwork. We only got round to processing eleven.” That was the bitter irony of it; by trying to follow the rules, these unlucky eleven home owners had created a paper trail that Junta officials could follow back to specific properties.

Time was ticking on. The crowd was getting angrier, the shouting louder. More Guardia officers arrived. Danny phoned everyone and anyone he could think of who was involved with the case.

It was the usual pass-the-parcel.

The council blamed the Junta, the Junta blamed the courts, the courts blamed the council; all down the line, each link of the chain shrugged its shoulders and pointed to someone else. Arthur Cooke watched Danny in action, hoping that this man who spoke such perfect Spanish could somehow work a miracle. Danny finished the phone call, shook his head. The flicker of light in the old man’s eyes dulled.

Paco Pino arrived at 11 a.m., yawning and scratching at his chest. “My one day off,” the photographer said, screwing a lens onto one of three cameras dangling from his neck, “And this has to go and happen. Just my luck.”

Danny was glad the Cookes couldn’t speak Spanish; crass comments like that were the last thing they needed to hear. Not that Paco was a bad person; experience had simply made him blasé, like everyone who made a living reporting other people’s misfortunes. Truth be told, Paco was a saint in comparison with some; Danny had spoken to one of the journalists sent by a UK red top to cover the announcement of the demolition orders the previous year.

“We won’t be interested again now until they knock the things down,” she said as she left, nodding toward the cloudy March sky. “Let’s hope they do it in summer, eh? I might get a bit of a tan.”

The pile around the palm tree grew: beds, sofas, lampshades, mirrors, cardboard boxes stuffed with clothes and crockery. Danny looked at his watch. Not long now.

At ten to twelve, uniformed officers of the Policia Local cleared the last of the protestors from the garden and checked no one was left inside the house. There were more scuffles on the white gravel outside the villa, more insults in English and Spanish. The property’s black gates had been lifted from their hinges earlier to allow the excavator through. Having shoved a final protestor outside, Guardia Civil officers formed a human barrier in the space between the gateposts. Protestors waved paperwork at the Junta woman as she looked at her watch and waved toward the workers.

The sudden roar of the excavator’s engine caused everyone to freeze and fall silent. The crowd turned as the engine revved and the excavator’s mantis arm uncoiled and rose above the house. For a moment, time seemed stilled…

…and then the air thundered as the excavator’s claw drove down through the roof. An angry moan emerged from the crowd as the arm rose and hundreds of dislodged tiles showered and smashed on the ground. The excavator arm dipped once, twice, three times more, prising the roof apart before ripping backwards and pulling free a ragged-edged section of brickwork. Looking through the jagged rent it created was surreal; the neatly-tiled interior walls had been exposed, giving a view inside a giant dolls’ house.

The Cookes stood holding each other: Peggy sobbing; Arthur straining to keep her on her feet, his face stoic. They were tearing his house down, but he wouldn’t show a flicker of weakness. Another huge section of wall tumbled away; it fell to the ground with a thud. Dust rose, people coughed, choked, began walking back along the road. Danny pulled his jacket up to cover his mouth.

The Spanish woman atop the ridge didn’t really care about the foreigners; their house was illegal; it had to come down.

She was only there for the spectacle, to have something to tell her friends tomorrow at the market.

She was the first to see it.

Her mouth gaped; then she began to scream and point toward the corner of the house. People looked to see what the noise was but the sounds were rendered unintelligible by the rumble of falling brickwork and the excavator’s diesel chug.

But the dust was settling now; people were following the woman’s outstretched hand, squinting as they too noticed the thing wedged in the narrow gap between exterior and interior wall.

A Guardia Civil officer rushed to the excavator, banged on the window. The machine fell silent. Other people had noticed the shouting woman now and were pressing closer, shading their eyes, unsure of what they were seeing. For the second time that morning, a sudden silence halted the crowd.

Danny thought it was a mannequin at first. And then the corpse fell forward, bending from the waist, its blackened head rocking back and forth. Some people screamed; others stood open-mouthed; some turned to run.

Arthur Cooke’s face remained expressionless as he stared at the semi-skeletal corpse lolling from the broken wall of his house. Then, without moving a single muscle of his face, he toppled forward and fell heavily to the earth.

Need to know what happens next? Get Scarecrow now from Amazon.

My books centre around the early years in the reign of Elizabeth I (the 1560s), which I studied when I earned my doctorate in sixteenth-century English history. I live in York, within a stone’s throw of King’s Manor. This was the building where Henry VIII stayed in 1536, and his suite of rooms is now one of the University of York’s libraries. If you stand at the back of the building, you can see a tiny window that leads to nowhere: it originally let some light into Henry’s specially-made toilet, or garderobe.

My books centre around the early years in the reign of Elizabeth I (the 1560s), which I studied when I earned my doctorate in sixteenth-century English history. I live in York, within a stone’s throw of King’s Manor. This was the building where Henry VIII stayed in 1536, and his suite of rooms is now one of the University of York’s libraries. If you stand at the back of the building, you can see a tiny window that leads to nowhere: it originally let some light into Henry’s specially-made toilet, or garderobe.

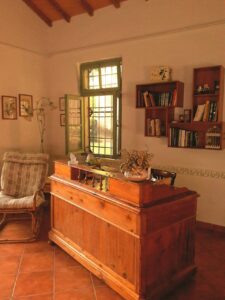

The beauty of having a laptop is that it is mobile. I have written in cafés, on trains, on picnic tables by the sea, and in hotels — but the real work, the editing, polishing and research, happens at my desk, ignoring the blank brick wall.

The beauty of having a laptop is that it is mobile. I have written in cafés, on trains, on picnic tables by the sea, and in hotels — but the real work, the editing, polishing and research, happens at my desk, ignoring the blank brick wall.

My writing rituals are more mundane and less … smelly. I start with two (not one, not three) cups of coffee. I keep a stuffie of Curious George on my desk, in honour of Curious George Rides a Bike, the first book I read cover-to-cover. I say hello to George each morning.

My writing rituals are more mundane and less … smelly. I start with two (not one, not three) cups of coffee. I keep a stuffie of Curious George on my desk, in honour of Curious George Rides a Bike, the first book I read cover-to-cover. I say hello to George each morning.

Just to complicate matters, when you set your crime in a historical context, you’ve got to find out what your medical man would have known at that time. Which isn’t what he knows now by a long chalk. At which point, thank heavens for the internet!

Just to complicate matters, when you set your crime in a historical context, you’ve got to find out what your medical man would have known at that time. Which isn’t what he knows now by a long chalk. At which point, thank heavens for the internet!