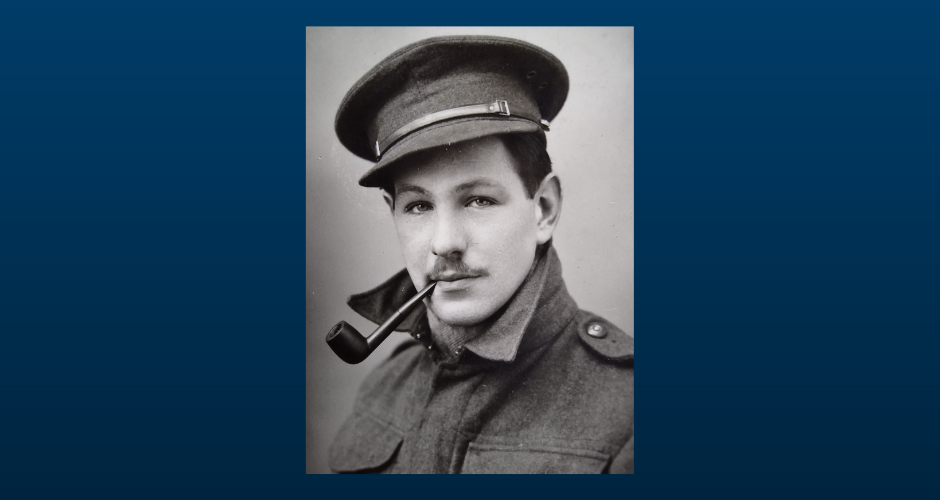

Captain Stanley Pavillard, author of Bamboo Doctor, served as a Medical Officer with the Straits Settlements Volunteer Forces during World War Two. When taken as a POW of Japan in 1942, he used his skills as a doctor to save the lives of many of his fellow prisoners, who were forced to work on the infamous Bangkok–Burma railroad. To commemorate the eightieth anniversary of the end of World War Two, his granddaughter Vanessa shares her memories of him below.

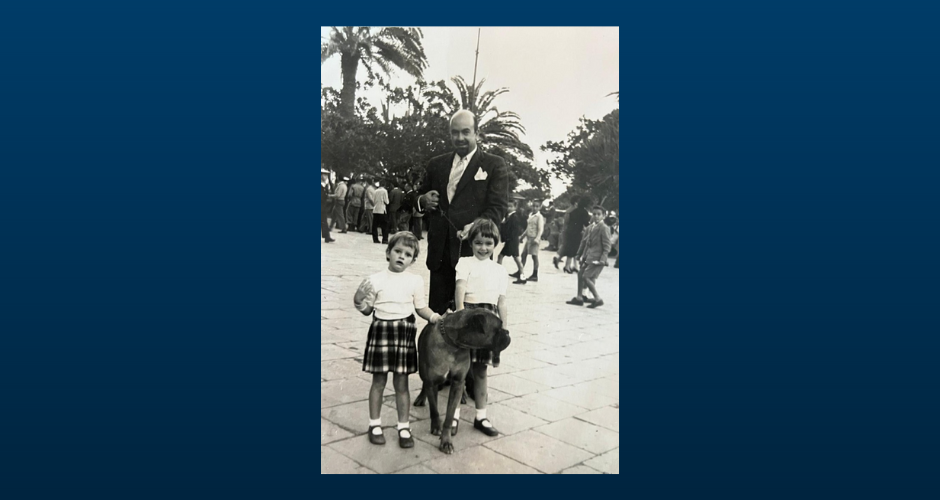

A lot can be found on Stanley Pavillard online about his early life, his achievements during the war and his career as a doctor. What is less talked about, for obvious reasons, is his private family life. Stanley was a father to three daughters, Linda (my mother), Anita and Sandra. His wife, Irene, an extraordinarily witty and funny lady, remained in his shadow most of her life but shone equally bright in our hearts with her unique style.

Although a proud war hero, Stanley was marked by the war in ways that even I, as a five-year-old grandchild could notice. Due to lack of proper nutrition and vitamins in the camps, Stanley’s eyesight slowly deteriorated over the years to the point where he had very limited tunnel vision. As children, we were always told very strictly to move any toys out of the way or Grandpa might slip on them and fall. Another memory my mum shared with me is that Stanley told his daughters never to touch him while he was asleep. Out of fear of being attacked in his sleep, he had developed a hypervigilance during his time in the POW camps and would jump at any sound or movement. One night, little Linda forgot, touched her sleeping dad and to her surprise got a tight slap!

There were happy and funny memories too, of course, such as the big parties he would throw at the extravagant house he built for the family. I remember my grandfather surrounded by lots of guests and children, doing his favourite trick of hiding his hand in his sleeve and pulling it out suddenly with a loud roar to scare everyone. We couldn’t get enough of his tricks and jokes. Stanley had a sense of drama and a charisma that was hard to ignore. As a child I was both fascinated and terrified when I had a stomach-ache and would finally be brought to him for consultation. He would make me lie down and press his hands carefully against my tummy. The cure felt instant every time.

Stanley marked a generation or maybe even two with his tremendous work in saving so many lives during the war. My mum remembers the countless letters the family would receive at Christmas: Thank you, Pav, for saving my life. The love, generosity and compassion he radiated during those extremely hard times have marked history, together with all his fellow soldiers and prisoners who endured the war. What he left behind, and maybe passed on, is a capacity for adapting and surviving in the hardest situations, thanks to creativity and perseverance, as well as a willingness to move forward and create a life after traumatic events. Equipped with all these skills, our job as his family is to not only survive in a world that is complex in different ways but to thrive and work towards even better times.

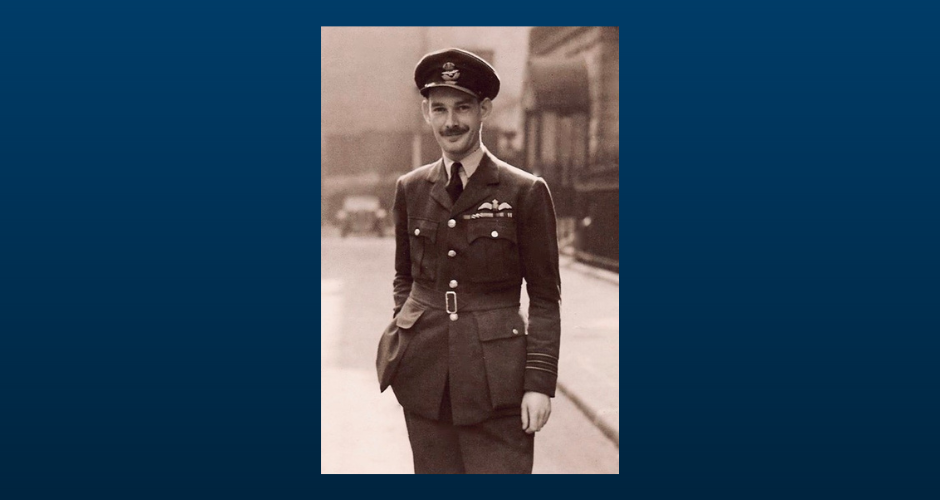

1945, he was confident that the war was soon to conclude. His mood on VE Day as an optimistic family man would have no doubt been a mixture of pride and reflection. He would have been proud of his achievements: he’d been made leader of the 141 Wing at Deanland only the year before, and had been awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and Two Bars as a flying ace. He would have been reflecting on his numerous wartime adventures, from the Battle of Britain to his time in North Africa, Italy and many other countries. Bobby’s mood on VE Day likely matched the mood of many of ‘The Few’, and I have no doubt he would have felt joy at the war’s conclusion.

1945, he was confident that the war was soon to conclude. His mood on VE Day as an optimistic family man would have no doubt been a mixture of pride and reflection. He would have been proud of his achievements: he’d been made leader of the 141 Wing at Deanland only the year before, and had been awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and Two Bars as a flying ace. He would have been reflecting on his numerous wartime adventures, from the Battle of Britain to his time in North Africa, Italy and many other countries. Bobby’s mood on VE Day likely matched the mood of many of ‘The Few’, and I have no doubt he would have felt joy at the war’s conclusion.

My father’s book began decades later, assembled from scraps of his diary, postcards, and letters sent through the Red Cross, all of which he had kept hidden away in a shoebox. On page seven of the first edition, you’ll find his death certificate — the Office of the Cheshire Regiment officially reported him killed in action in May 1940. It took months for news of his survival to reach home. That certificate became for me the most vivid proof that life indeed is hanging in the balance.

My father’s book began decades later, assembled from scraps of his diary, postcards, and letters sent through the Red Cross, all of which he had kept hidden away in a shoebox. On page seven of the first edition, you’ll find his death certificate — the Office of the Cheshire Regiment officially reported him killed in action in May 1940. It took months for news of his survival to reach home. That certificate became for me the most vivid proof that life indeed is hanging in the balance.

In 2025, we republished Years Not Wasted. It’s more than a memoir — it’s a witness statement. It honours ordinary soldiers who endured extraordinary hardship. It is a uniquely authentic book, told in the way it was recorded in letters and a diary at the time, rather than reconstructed from fallible memory. It was written to share the knowledge “soon acquired once war has started that the cost, in lives, in grief, in suffering, is immeasurable, and unacceptable however much one did accept it at the time.” It’s a call to remember how people like my father built their lives after war, choosing patience over bitterness, solidarity over division, peace over conflict. For my father, it was always about taking one step at a time, drawing from patience and reflection. That is the lesson I carry forward.

In 2025, we republished Years Not Wasted. It’s more than a memoir — it’s a witness statement. It honours ordinary soldiers who endured extraordinary hardship. It is a uniquely authentic book, told in the way it was recorded in letters and a diary at the time, rather than reconstructed from fallible memory. It was written to share the knowledge “soon acquired once war has started that the cost, in lives, in grief, in suffering, is immeasurable, and unacceptable however much one did accept it at the time.” It’s a call to remember how people like my father built their lives after war, choosing patience over bitterness, solidarity over division, peace over conflict. For my father, it was always about taking one step at a time, drawing from patience and reflection. That is the lesson I carry forward.