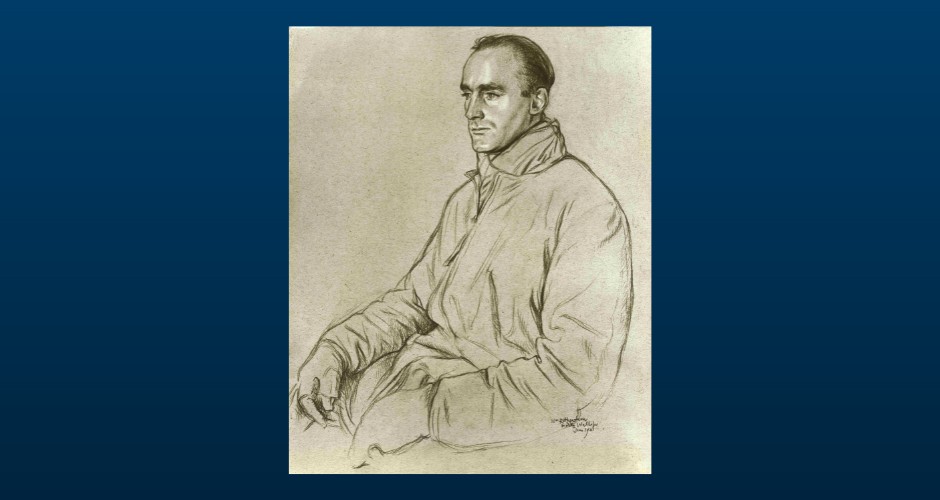

Air Commodore Roderick Chisholm, CBE, DSO, DFC & Bar (1911–1994), author of Cover of Darkness, was a night fighter pilot, flying ace and a highly decorated British airman of the Second World War. To commemorate the eightieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War, his son Julian reflects on his father’s life in 1945.

In 1930 Roderick Chisholm joined 604 Squadron of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. He learnt to fly and was commissioned as an officer. He left the squadron in 1935 when his work took him to Iran. Before rejoining his squadron in late June 1940, he took a refresher course to become a night fighter pilot and fly the squadron’s Blenheims. During the war, while flying Beaufighters and Mosquitos, he shot down nine enemy aircraft with the assistance of his airborne observers and the ground controllers, he commanded the Night Fighter Interception Unit at Ford, and was the second-in-command of Bomber Command’s 100 Group, which was charged with defending RAF bombers over enemy territory. He recorded his wartime experiences in Cover of Darkness, which was first published in 1953.

Immediately after hostilities ended, Roderick led a team of twelve charged with gaining as much intelligence as possible about the impact of 100 Group’s radar-assisted night fighters, Mosquitos, and Radio Counter Measures. The team did their work at the final base of the Luftwaffe in Schleswig, just before it was disbanded and its personnel transferred to POW camps. They carried out interrogations of Luftwaffe night fighter commanders and pilots, observers, flight controllers and technicians, held technical discussions, and examined the vast number of German aircraft parked on the airfields. The team gained confirmation of the effectiveness of 100 Group’s efforts, and had the satisfaction that as a result RAF losses were significantly reduced. The Mosquito had an awesome reputation amongst the German airmen.

Major Schnauffer was one of the pilots whose interrogation Roderick witnessed. Schnauffer was a brave and skilful night fighter pilot who was credited with shooting down no less than 124 bombers in defence of his country. He wore uniform, and on the last day the Germans were allowed to wear medals, he wore the highest order of the Iron Cross around his neck. The exchanges with the Germans were generally civilised and friendly, but my father could not ignore that they were Nazis, and that nearby were camps for Russian prisoners living in ghastly conditions, and mini-Belsens for Jews and other displaced persons.

Major Schnauffer was one of the pilots whose interrogation Roderick witnessed. Schnauffer was a brave and skilful night fighter pilot who was credited with shooting down no less than 124 bombers in defence of his country. He wore uniform, and on the last day the Germans were allowed to wear medals, he wore the highest order of the Iron Cross around his neck. The exchanges with the Germans were generally civilised and friendly, but my father could not ignore that they were Nazis, and that nearby were camps for Russian prisoners living in ghastly conditions, and mini-Belsens for Jews and other displaced persons.

Roderick’s mission complete, he flew back to Norfolk. While doing so, he envisioned a future Europe in which frontiers would mean no more and individual nationalities were less important, as per the multi-national squadrons of the Battle of Britain. After the collapse of France in 1940, British, French, Belgian, Czech, Polish and other nationalities had flown in harmony in polyglot fighter squadrons. Their aims were identical, and their understanding effective thanks to the basic English of the radio. Sadly, later, as national squadrons were formed, national identities asserted themselves and the unity achieved in the Battle of Britain became compromised.